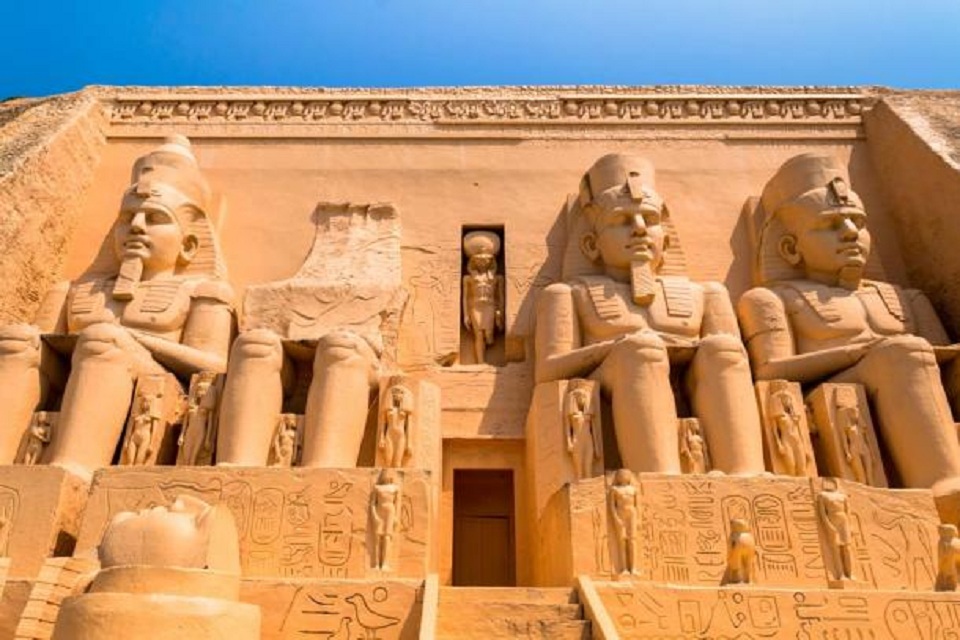

Carved out of the mountain on the west bank of the Nile between 1274 and 1244 BC, this imposing main temple of the Abu Simbel temple was as much dedicated to the deified Ramses II himself as to Ra-Horakhty, Amun and Ptah. The four colossal statues of the pharaoh, which front the temple, are like gigantic sentinels watching over the incoming traffic from the south, undoubtedly designed as a warning of the strength of the pharaoh.

Over the centuries both the Nile and the desert sands shifted, and this temple was lost to the world until 1813, when it was rediscovered by chance by the Swiss explorer Jean-Louis Burckhardt. Only one of the heads was completely showing above the sand, the next head was broken off and, of the remaining two, only the crowns could be seen. Enough sand was cleared away in 1817 by Giovanni Belzoni for the temple to be entered.

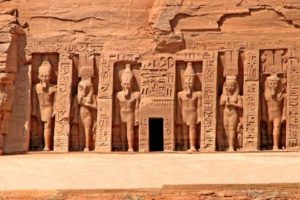

From the temple’s forecourt, a short flight of steps leads up to the terrace in front of the massive rock-cut facade, which is about 30m high and 35m wide. Guarding the entrance, three of the four famous colossal statues stare out across the water into eternity – the inner left statue collapsed in antiquity and its upper body still lies on the ground. The statues, more than 20m high, are accompanied by smaller statues of the pharaoh’s mother, Queen Tuya, his wife Nefertari and some of his favourite children. Above the entrance, between the central throned colossi, is the figure of the falcon-headed sun god Ra-Horakhty.

The roof of the large hall is decorated with vultures, symbolising the protective goddess Nekhbet, and is supported by eight columns, each fronted by an Osiride statue of Ramses II. Reliefs on the walls depict the pharaoh’s prowess in battle, trampling over his enemies and slaughtering them in front of the gods. On the north wall is a depiction of the famous Battle of Kadesh (c 1274 BC), in what is now Syria, where Ramses inspired his demoralised army so that they won the battle against the Hittites. The scene is dominated by a famous relief of Ramses in his chariot, shooting arrows at his fleeing enemies. Also visible is the Egyptian camp, walled off by its soldiers’ round-topped shields, and the fortified Hittite town, surrounded by the Orontes River.

The next hall, the four-columned vestibule where Ramses and Nefertari are shown in front of the gods and the solar barques, leads to the sacred sanctuary, where Ramses and the triad of gods of the Great Temple sit on their thrones.

The original temple was aligned in such a way that each 21 February and 21 October, Ramses’ birthday and coronation day, the first rays of the rising sun moved across the hypostyle hall, through the vestibule and into the sanctuary, where they illuminate the figures of Ra-Horakhty, Ramses II and Amun. Ptah, to the left, was never supposed to be illuminated. Since the temples were moved, this phenomenon happens one day later.